This transcript has been edited for clarity.

welcome to Impact factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As some of you may know, I do a lot of clinical research to develop and evaluate artificial intelligence (AI) models, particularly machine learning algorithms that predict certain outcomes.

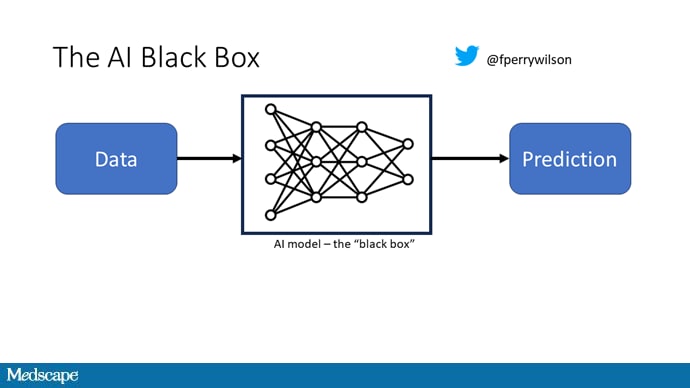

A thorny issue that arises as algorithms become more complex is “explainability.” The problem is that AI can be a black box. Even if you have a very accurate model to predict death, clinicians don’t trust it unless you can explain it. how he makes his predictions – how it works. “It works” is not enough to build trust.

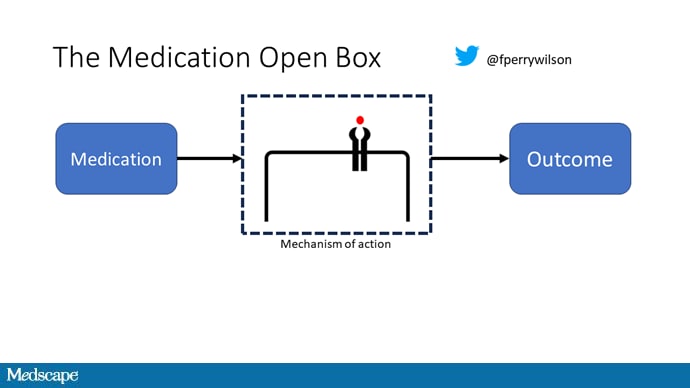

It is easier to build trust when talking about a drug rather than a computer program. When a new blood pressure medication comes on the market that lowers blood pressure, we know Why it lowers blood pressure. Every drug has a mechanism of action, and for most of the drugs in our armamentarium, we know what that mechanism is.

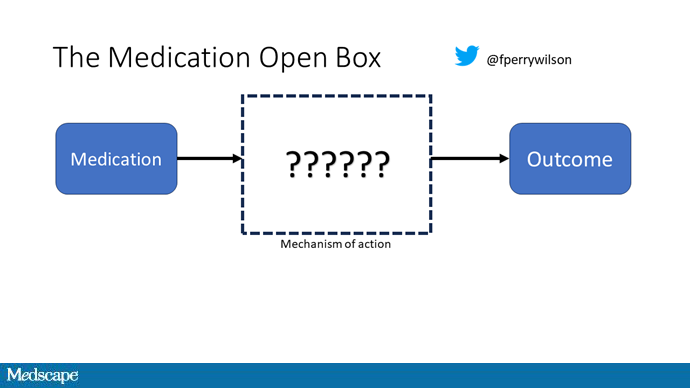

But what if there was a drug – or better yet, a treatment – that worked? And I can honestly say that we have no idea how this works. This is what came across my desk today in what I believe to be the largest and most rigorous trial of a traditional Chinese medicine in history.

“Traditional Chinese medicine” is an omnibus term that refers to a class of therapies and health practices fundamentally different from the way we practice medicine in the West.

It is a highly personalized practice, with practitioners using often esoteric means to choose which substance to administer to which patient. This personalization makes traditional Chinese medicine almost impossible to study in the typical randomized trial setting, because treatments are not chosen based solely on disease states.

The lack of scientific rigor in traditional Chinese medicine means that it is full of practices and beliefs that can legitimately be described as pseudoscience. As a nephrologist who has treated someone for “Chinese herbal nephropathy“I can tell you that some practices can be actively harmful.

But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing. I don’t subscribe to the “antiquity argument” – the idea that because something has been done for a long time, it must be correct. But at the same time, traditional and non-science-based medicine practices could still identify effective therapies.

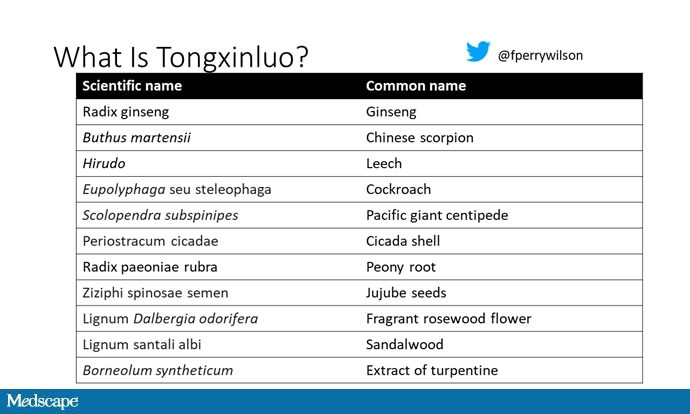

And with that, let me introduce Tongxinluo. Tongxinluo literally means “to open the network of the heart”, and it is a substance used for centuries by practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine to treat angina but its use was approved by the Chinese National Medicine Agency in 1996.

Today we will review a large randomized trial of Tongxinluo for the treatment of ST-segment elevation. myocardial infarction (MID), appearing in JAMA.

Like many traditional Chinese medicine preparations, Tongxinluo is not a simple chemical product, far from it. It is a powder made from a variety of plant and insect parts, as you can see here.

I can’t imagine giving this concoction a try in the United States; I just don’t see an institutional review board approving it, given the ingredient list.

But let’s put that aside and talk about the study itself.

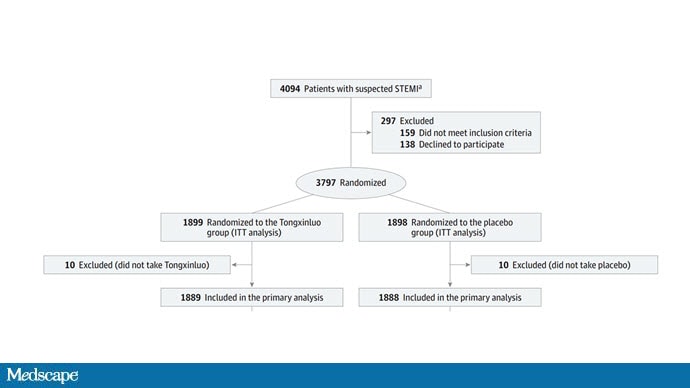

Although I do not have access to any primary data, the wording of the study suggests that it was very rigorous. Chinese researchers randomized 3,797 patients with ST-segment elevation MI to take Tongxinluo – four capsules, three times a day for 12 months – or a matching placebo. The placebo was designed to look like Tongxinluo capsules and, if the capsules were opened, to also smell like them.

Researchers and participants were blinded and statistical analysis was carried out by both the main team and an independent research agency, also in China.

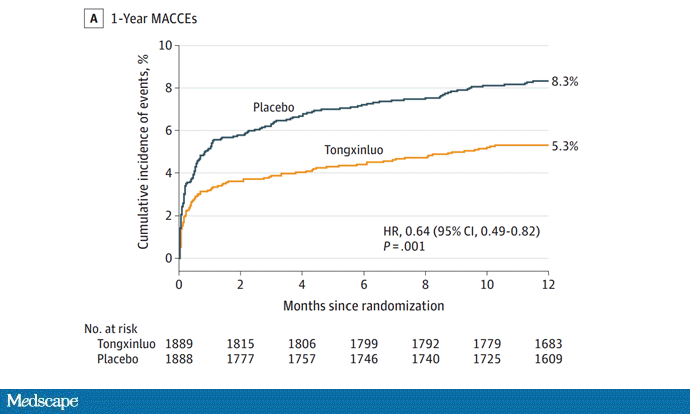

And the results were pretty good. The primary outcome, major cardiovascular and cerebral events over 30 days, was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the placebo group.

The one-year results were just as good; 8.3% of the placebo group experienced a major cardiovascular or cerebral event during this period, compared to 5.3% of the Tongxinluo group. In short, if it were a pure chemical compound from a big pharmaceutical company, well, you might see a new heart attack treatment – and an increase in stock price.

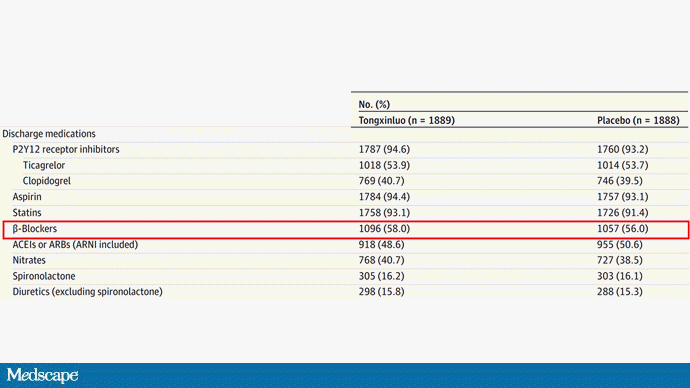

But there are some problems here, with generalizability being a major problem. This study was conducted entirely in China, so its applicability to a more diverse population is unclear. Additionally, the quality of post-MI care in this study is much worse than what we would see here in the United States, with just over 50% of patients discharged on a beta blocker, for example.

But issues of generalizability and potentially substandard complementary treatments are the problem. usual reasons why we worry about new drug trials. And those concerns seem to pale in comparison to the big concern that I have here, which is that, you know, we don’t know why this works.

Does the leech extract in the preparation perhaps thin the blood a little? Or is it the antioxidants in ginseng, or something from the Pacific centipede or sandalwood?

This essay does not strike me as a vindication of traditional Chinese medicine, but rather an example of a missed opportunity. More rigorous scientific study over the centuries of the use of Tongxinluo might have identified one, or perhaps several, compounds with strong therapeutic potential.

The purity of medical substances is extremely important. Pure substances have predictable effects and side effects. Pure substances interact in predictable ways with other treatments we give to patients. The purity of pure substances can be quantified by third parties, they can be manufactured according to accepted standards, and their adulteration can be assessed. In short, pure substances present fewer risks.

Now, I know this can sound particularly sterile. Some people will think that a “natural” substance has inherent advantages over pure compounds. And of course, there is something calming about imagining a traditional preparation passed down over centuries, carefully prepared by a single practitioner, as opposed to the sterile industrial processes of a for-profit pharmaceutical company. I understand. But natural does not equal safety. I am happy to have access to aspirin and I don’t need to chew willow bark. I like my penicillin pure and am glad I don’t have to make mold slurry to treat a bacterial infection.

I commend the researchers for subjecting Tongxinluo to the rigor of a well-designed trial. They generated incredibly interesting data, but not because we have a new treatment for ST-segment elevation MI; it’s because we have a map to a new treatment. The next big thing in heart attack care isn’t the blend that Tongxinluo is, but it could be. in the mixture.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Yale Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communications work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How medicine works and when it doesn’t work, is available now.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), InstagramAnd Youtube