WHEN Lucy Foulkes Growing up, young people didn’t talk about their mental health. Today things are very different. Mental health awareness days are numerous, the language of psychiatry has become part of the vernacular and, in some countries, schools have become the front line for young people’s mental health problems.

Still, Foulkes doesn’t believe things have necessarily changed for the better. As a psychologist at the University of Oxford, she argues that this societal push to talk about our mental health may not help everyone. In fact, it might make things worse. She speaks to New scientist about how “concept drift” and “therapeutic discourse” are doing people a disservice when it comes to mental health.

Catherine de Lange: It seems like there is a mental health awareness campaign almost every week. Surely that’s a good thing?

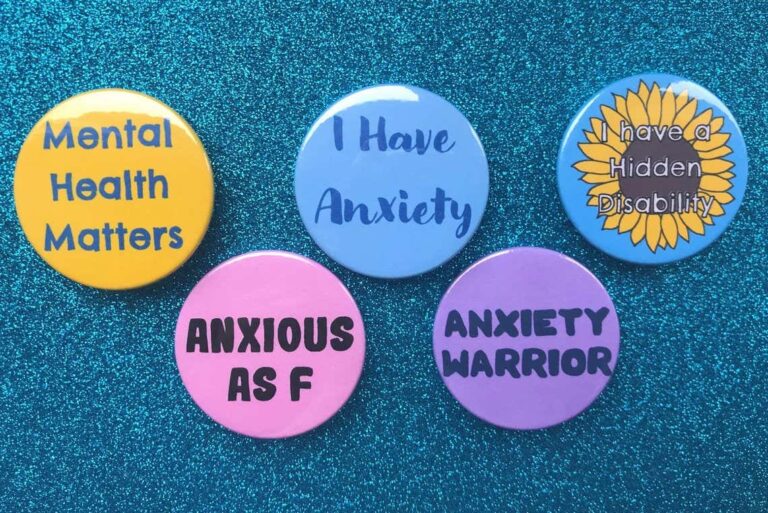

Lucy Foulkes: It seems like it is, but I think there are all sorts of reasons why that might not be the case. These campaigns are often designed for social media, posters, billboards or the like, so they are necessarily very superficial when in reality, mental health is an incredibly complex subject. They tell people to go get help, and often the help isn’t there. Many campaigns encourage people to talk and not enough teach them to listen.

What I’m really interested in is whether they encourage people to essentially interpret all negative thoughts and feelings as symptomatic of a disorder or problem. This has serious consequences: people feel unnecessarily vulnerable and consider themselves to have a disorder when they are not.