Ghana is the latest African country to commit to GMOs with the aim of reaping economic benefits from agriculture.

SPECIAL FILE | BIRD AGENCY | The designation of Ghana as an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Collaborating Center for Africa, focused on plant breeding and associated technologies for food and nutrition, is seen as a pivotal moment in the application of genetic modification in Africa.

In a recent press release, the IAEA announced its collaboration with the Biotechnology and Nuclear Agriculture Research Institute (BNARI) of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission, as part of a four-year engagement “ aimed at promoting research and development on mutation selection in West and Sub-Saharan Africa. Africa.”

Najat Mokhtar, IAEA Deputy Director General and Head of the Department of Nuclear Applications, called mutation breeding a powerful tool to address the global challenge of food security.

“This allows us to develop food crops with increased yields, improved nutritional quality and enhanced resilience to climate change. Through our closer collaboration with BNARI, we aim to share our expertise and build capacity to deploy this safe and highly effective technique in a wider geographical region,” she explains.

BNARI is set to become the IAEA’s first African Collaborating Center in plant breeding and genetics, one of only six such centers in the world, and was chosen for its strategic location and its expertise in radiation-induced mutations.

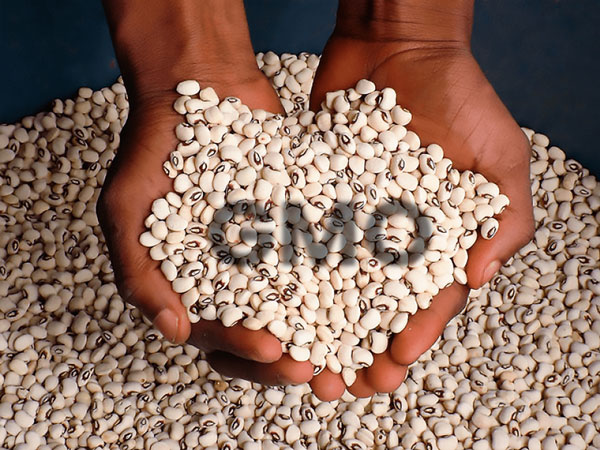

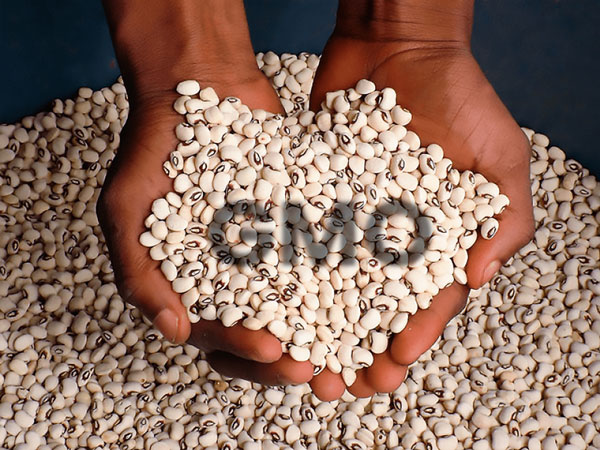

In recent times, Ghana has been at the forefront of adopting genetic modification technology to improve crop and plant species. The country is set to introduce its first genetically modified cowpea, developed by the Savannah Agriculture Research Institute (SARI), into the Ghanaian market this year.

Projections indicate that this modified cowpea will significantly increase yields – by almost 300 percent. Jerry Nboyine, a senior researcher at SARI, pointed out in an interview on GhanaWeb that the modified variety does not require the use of insecticides, unlike non-GMO cowpea.

Ghana is one of a small but growing number of African countries that have adopted genetic modification technology to boost agricultural productivity and resilience. The International Agro-Biotechnology Applications Acquisition Service (ISAAA) estimates this number to be three in 2016, and more than ten in 2022.

Kenya last year lifted a decade-old ban on genetically modified crops, now allowing their cultivation, research and importation of certified GM crops and animal feed.

South Africa, Nigeria, Malawi, Sudan, Uganda, Burkina Faso, Egypt and Sudan have all adopted the technology and many have conducted field trials.

Nigerian academic Ademola Adenle weighed in on the subject in an analysis published by “The Conversation” in June, arguing that genetically modified crops offer a powerful solution to Africa’s pressing food crisis.

“Based on my research in this area, I believe that agricultural innovations such as genetically modified crops or organisms have the potential to contribute to food security in Africa,” he explained.

The food crisis in Africa cannot be underestimated, and it extends beyond hunger, encompassing nutritional deficits that have been exacerbated by erratic climatic conditions resulting from human-induced local and global climate change, as well as logistical challenges.

UNFAO’s 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition Report reveals a worrying increase in global hunger, with more than 122 million additional people facing hunger since 2019. A significant portion of this Growth is occurring in Africa, where nearly 20% of the population faces hunger.

Additionally, the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) in Africa increased from 19.4 percent in 2021 to 19.7 percent in 2022, mainly due to an increase in North and Southern Africa.

South Africa and Sudan are already considered pioneers in the application and use of genetically modified technologies to accelerate agricultural production, mainly maize in South Africa and cotton in Sudan. South Africa has seen a significant increase in maize production, even in years of low rainfall, which regularly results in a surplus that earns the country foreign exchange when exported.

“Research showed that 65% of the gains came from higher yield and production and 35% from lower costs,” says Adenle, emphasizing the economic value of planting genetically modified crops.

The Rainbow Nation has been growing genetically modified maize commercially since 1997. A 2021 study published in ScienceDirect, titled “Economic and ecosystem impacts of genetically modified maize in South Africa” found that genetically modified maize had generated social benefits exceeding $694 million between 2001 and 2018.

“We started planting GMO corn seeds during the 2001/2002 season. Before their introduction, average maize yields in South Africa were around 2.4 tonnes per hectare. This increased to an average of 6.3 tonnes per hectare in the 2022/23 production season,” explained Wandile Sihlobo, a South African agricultural economist.

As extreme weather disrupts agricultural patterns, recent genetic modifications have focused on indigenous crops such as cassava and sweet potato, which are more resilient to climate change.

Several other agencies across Africa have actively advanced these technological solutions. A prime example of this is the Pan African Bean Research Alliance (PABRA), which revealed last week that it has researched, developed and distributed more than 650 new bean varieties across 32 countries.

PABRA’s efforts have led to a 30% increase in income for more than five million households in ten countries, and farmers who grow, consume and sell its beans are 6% more likely to achieve food security and 6 % less likely to live in poverty. .

As Adenle explained, to increase yields, countries should invest more in biotechnology research, train scientists, involve local experts in decision-making, encourage government collaboration, and use science-based communication to raise awareness. both the benefits and concerns surrounding genetically modified crops.

*****

SOURCE; Bonface Orucho, bird story agency