Kathleen Tierney has always lived life on the fly. In a career that spanned more than four decades, Tierney dedicated her life to coaching and then an athletic administrator, serving as athletic director at Bryn Mawr College. After 15 years at the Philadelphia area school, she retired in the summer of 2022.

Amid her hectic post-retirement routines of walking her dog and riding her bike, Tierney, who had made fitness a priority in her personal and professional life, found herself extremely out of breath after exercising. From there, things only got worse. “I couldn’t even walk up a flight of stairs without getting out of breath. My heart would feel like it was racing…and then it would slow down. It was debilitating,” Tierney recalls.

Tierney made an appointment with a cardiologist who diagnosed him with atrial fibrillation, more commonly known as AFib. AFib – the most common type of heart arrhythmia – occurs when your heart’s electrical signals start to misfire. Instead of beating at a steady pace, the upper chambers of the heart (the atria) begin to quiver or flutter irregularly. When your heart is in AF, the blood in the atria is not pumped properly. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention predicts that more than 12 million Americans will have atrial fibrillation by 2030.

Several tests were deployed to identify factors contributing to his Afib. The guilty? A faulty mitral valve, one of the four valves of the heart that is involved in the timing and direction of blood flow. Her cardiologist referred her to Michael Ibrahim, MD, MBBS, PhD, director of mitral valve and reconstructive surgery at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, specializing in mitral valve surgeries, particularly with the use of robotics.

Tierney, who had already overcome breast cancer years before, was determined to take on this new challenge and have her mitral valve repaired.

A focus on recovery

Ibrahim came onto the scene with a solution to Tierney’s faulty mitral valve: robotic mitral valve repair.

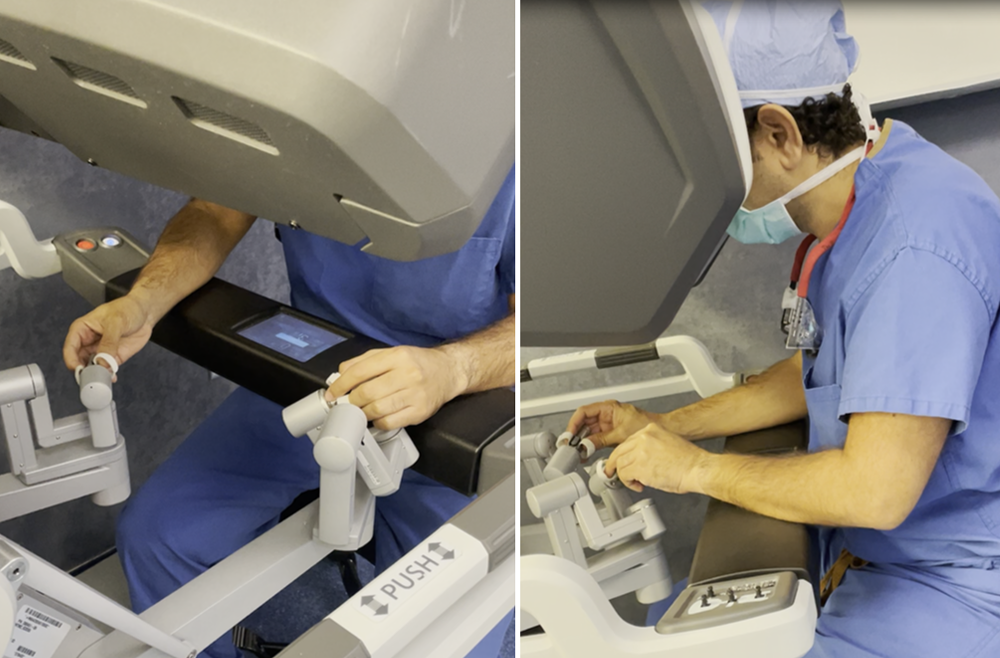

“This type of surgery constitutes the ultimate minimally invasive cardiac surgery. It allows maximum dexterity, valve visualization and tissue manipulation with very small incisions,” Ibrahim said. The innovative procedure involved tiny 5mm incisions, eliminating the need to spread the ribs.

Tierney saw this opportunity because recovery time with robotic surgery was typically much quicker because the sternum did not need to be broken to access the heart. According to Ibrahim, the sternum can take six months to a year to fully heal, and in some patients it never fully heals.

“Recovery was a very important factor for me moving into robotics. The robot was much simpler. They didn’t need to cut open my chest. There are five small incisions under my right arm, where the robot went in,” she recalls.

In January 2023, she arrived at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center for her surgery, confident and comfortable with what she was about to endure. “Dr. Ibrahim did a very good job balancing the ego and the humanistic approach. I felt like he really cared about me and the outcome. He was so committed to this procedure after his years of experience conducting this type of surgery,” she said.

Ibrahim noted that Tierney needed complex mitral valve repair, adding that “most people have disease affecting only one of the mitral leaflets, but Kathleen had severe degenerative disease of both leaflets.”

“Another component we added was a Maze procedure. This is an ablation in which we use high energy to create scars in the heart designed to reduce the chances of atrial fibrillation.

Using robotics compared to traditional mitral valve surgery does not reduce the time spent on the operating table, but Ibrahim says the robot allows for greater precision during the operation and much greater recovery. fast, as Tierney demonstrated: “I was in the intensive care unit for a day and a half and was released from the hospital four days after the operation,” he said. she declared. After a few weeks of cardiac rehabilitation, she felt well enough to resume her daily bike rides in spring 2023.

Ibrahim says this type of robotic mitral valve technology was developed about 15 years ago, but has matured rapidly over the past two or three years. Ibrahim, who joined Penn Medicine in 2015, played a key role in developing the robotics program here. Already, he says, robotic mitral valve surgeries far exceed the traditional mitral valve surgeries he performs. “My goal is to make our robotic mitral valve program the number one in the country,” he said.

Caring with compassion

Tierney, now 66, describes her experience as a testament to the possibilities of modern medicine, guided by Ibrahim’s steady hands and compassionate heart. “I feared that after being active my whole life, I would no longer be able to return to the life I had envisioned for myself,” she said. “He was so human and I connected with him in a way that surprised me. I really trusted him.

It is this bond that Ibrahim strives to establish with each of his patients. “My brother had heart surgery when I was little, and there was a lack of communication between his healthcare team and my family. I learned a lesson from it. People want to know the risks involved and I always tell them. But they also want to know that they are in experienced hands and that you are sure that they will get a good result,” Ibrahim said.

As Tierney embarked on a cycling adventure through Ireland’s breathtaking landscapes during the summer of 2023, she marveled at the journey she had undertaken. It’s a trip she didn’t think possible a year ago; unsure that she would be able to live the active life she so desperately hoped for when she retired. But now, thanks to Dr. Ibrahim and his team at Penn, with her beating heart and free spirit, she was now a living testament to the power of innovation, resilience, and the art of healing. “She is full of life and her entire care team was motivated to allow her to return to life at full speed,” explains Ibrahim.