The labels are intended to help consumers navigate more easily and make better choices at the grocery store. THE proposed rule would align the definition of “healthy” claim with current nutrition science, the updated version Nutrition Facts Label and the current Dietary Guidelines for Americansthe FDA said.

The agency is also developing a symbol that companies can voluntarily use to label food products that meet federal guidelines for the term “healthy.”

The announcement has arrived ahead of the White House conference on hunger, nutrition and health on Wednesday. The conference was the first of its kind since 1969, when a summit hosted by President Richard M. Nixon’s administration led to a major expansion of food stamps, school meals and other programs that were credited with reducing poverty. hunger nationwide and provided a critical safety net during the pandemic.

Once finalized, the FDA’s new system will “quickly and easily communicate nutrition information” through tools such as “star ratings or traffic lights to promote equitable access to nutrition information and healthier choices,” a statement said. the White House said in a statement this week. The system “can also incentivize industry to reformulate their products to be healthier,” it says, by adding more vegetables or whole grains or developing new products to meet the updated definition. day.

Six in ten American adults suffer from lifestyle-related chronic diseases, often due to obesity and poor diet. according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC says these diseases are the leading cause of death and disability and a leading cause of the nation’s $4.1 trillion in annual health care costs.

And the obesity epidemic is not moving in the right direction: Studies show that obesity, particularly among children, has increased significantly during the pandemic, with the biggest change among children ages 5 to 11, who gained an average of more than five pounds. Before the pandemic, about 36 percent of children ages 5 to 11 were considered overweight or obese; during the pandemic, this figure rose to 45.7 percent.

In In some Latin American countries, governments have instituted stricter food labeling laws, opposing sugary drinks and ultra-processed foods, in a bid to stave off the obesity epidemic who invaded the United States. In Chile, for example, foods high in added sugar, saturated fat, calories and added sodium must display black stop signs. on the front of their packages. Nothing with black stop signs may be sold or promoted in schools or included in television commercials aimed at children.

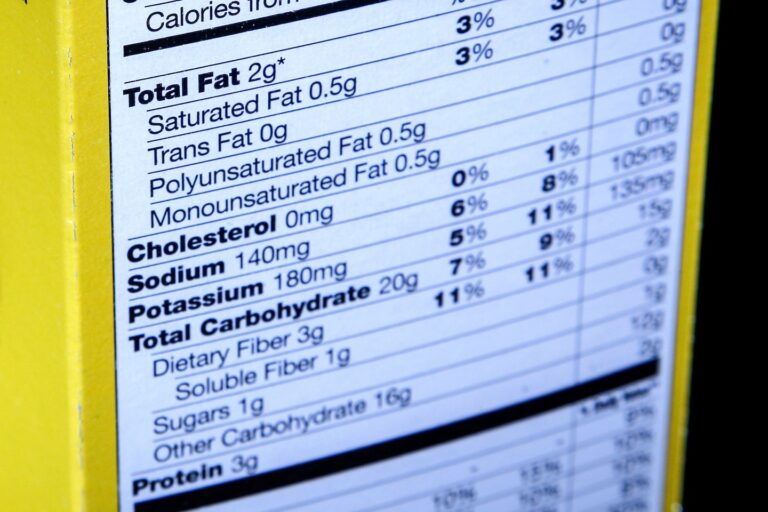

Groups such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest have long called for the FDA to adopt mandatory, standardized, evidence-based front-of-package labeling. They say front-of-package nutrition labeling will reach more consumers than back-of-package “nutrition information,” helping them quickly choose more beneficial foods and prompting companies to reformulate their products in a more beneficial direction. healthy. According to nutrition experts, Americans generally consume too much sodium, added sugars and saturated fats in their packaged foods. Being able to quickly identify foods rich or low in these nutrients would therefore be an important advantage for public health.

The Biden administration has endorsed the FDA’s efforts to combat sodium consumption, strengthening the agency’s role. announcement last year that it would require food companies and restaurants to reduce sodium in the foods they make by about 12 percent over the next two and a half years. In a parallel effort, the administration is suggesting the FDA reduce Americans’ sugar consumption by “including potential voluntary targets” for sugar content for food manufacturers.

The new labeling language is sure to be controversial among food manufacturers who have sought to capitalize on Americans’ interest in healthier foods.

“The FDA’s ‘healthy’ definition can only succeed if it is clear and consistent for manufacturers and understood by consumers,” Roberta Wagner, a spokeswoman for the industry organization Consumer Brands Association, said Tuesday.

But what constitutes a “healthy” diet is a thorny subject among nutrition experts. Would foods high in what many nutrition scientists call “good fats,” such as those containing almonds or avocados, be considered “unhealthy,” while artificially sweetened fruit snacks or low-fat sugary yogurts could be considered “healthy”?

The proposal is far from final and is likely to face some resistance from food manufacturers, who have sought in recent years to capitalize on consumers’ growing desire to eat healthier.

“In reality, the FDA’s proposed rule will need significant review and revision to ensure that it does not place food policy above science and facts,” Sean said McBride, founder of DSM Strategic Communications and former Grocery Manufacturers Association executive. “The details are crucial because the final rule goes far beyond a simple definition by creating a de facto nutrient profile regulatory system that will dictate how foods can be prepared for decades to come.”

Peter Lurie, executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, said front-of-package labeling holds great promise, but it needs to be mandatory, simple, nutrient-specific and include calories. . He said such labeling effectively changes consumer purchasing behaviors and forces companies to reformulate their products to achieve more favorable ratings. He said that unless a healthy definition and label is very specific, some companies will try to game the system by “health cleansing” their less healthy products to appear healthy.

The FDA has started a public process update the “healthy” nutritional content claim on food labeling in 2016. But critics said the dietary guidelines often failed to focus on the right things. Under the Trump administration, for example, the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Committee It was forbidden to consider the health effects of consuming red meat, ultra-processed foods and sodium.

Federal nutrition guidelines have seen significant pendulum swings. For many years, recommendations were based on intuitive but incorrect thinking: eating fat makes us fat. Consuming large amounts of cholesterol gives us high cholesterol levels.

First defined by the FDA in 1994, the term “healthy” initially focused on fat content. In 2015, the agency sent a warning letter to snack maker Kind over the company’s “healthy” label. A tissue? The bars, mostly nuts, were too high in saturated fat. Nutrition experts and Kind have submitted a formal petition to the FDA “to update its regulations regarding the term healthy when used as a nutritional content claim in food labeling” to reflect current science.

In 2016, the FDA reversed its position, allowing Kind to use the term “healthy” and announcing that the agency would reconsider the definition of the word.

New FDA guidelines announced this week would automatically allow whole fruits and vegetables to carry the “healthy” claim, and prepared food products would have to meet criteria for nutritional requirements and percentage limits for added sugars, sodium and saturated fats.

“Seven years after submitting our Citizen petition“Kind is pleased that the FDA has proposed an updated regulatory definition of ‘healthy,'” Kind CEO Russell Stokes said Wednesday. “A rule that reflects current nutrition science and dietary guidelines for Americans is a victory for public health – and it’s a victory for all of us.”

Recent dietary guidelines emphasize a plant-based diet, including vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds. They maintain a hard line on limiting your intake of salt and saturated fat, but they simply state that cholesterol is “not a nutrient of concern,” removing the long-standing limit of 300 milligrams per day.