The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed the extent to which health challenges are rooted in both global contexts and social inequalities. As of 2020, the infectious disease has spread around the world with breathtaking speed – even in high-income countries, which have been largely spared from previous major epidemics, including SARS, MERS or Ebola .

The Covid-19 pandemic has also shown that the risks of infection and access to healthcare (including vaccination) are extremely unequally distributed. This is true within societies as well as globally. In Germany, for example, certain groups were at particularly high risk of serious illness. They included older people as well as people with pre-existing conditions like obesity or diabetes mellitus. These health risks were linked to socio-economic factors. In particular, members of socially disadvantaged groups – such as people working in so-called systemically important sectors like nursing, construction or catering – were less able to protect themselves against infection.

In the global context, social and structural inequalities in health care and the ability to protect against serious infection have become equally evident. On the one hand, these inequalities have affected the resources of any given health system. People infected in India or Brazil, for example, often did not receive an adequate supply of oxygen. For another, vaccine shortage has become evident in low-income countries, many of which are in Africa.

Medical anthropology as a field of research

Covid-19-related questions regarding specific health risks from a social and demographic perspective as well as social and global inequality in access to health care are at the center of medical anthropology. Since the 1960s, this subfield of social and cultural anthropology has become the most important branch of the discipline, particularly in North America. This is seen in terms of teaching, research programs and areas of work.

Medical anthropologists study how gender, social background, and cultural norms shape perceptions of illness and well-being. They focus on how affected individuals experience specific health phenomena and examine how health issues are addressed in interaction with their respective personal networks. Relevant research questions include the prevention and treatment of physical and mental illnesses. Of course, reproductive health matters too.

Particularly in resource-poor regions of the world, people rely heavily on support from non-governmental organizations as well as extended families and local communities. This is less the case in industrialized countries, where many more people are covered by health insurance and formal health infrastructures are much stronger. However, there are also significant differences in health protection between high-income countries, for example between the welfare states of Northern Europe and the predominantly private health systems of North America.

Individual and collective experiences of health problems obviously depend on the conditions of the health systems in which they occur. Political and economic factors are therefore very relevant in the field of medical anthropology.

In high-income countries, inequalities in access to health care persist largely due to social, cultural and linguistic barriers. They greatly disadvantage migrants, for example. Global inequality is of particular concern in resource-poor countries that often rely on international financing. In many places, corporate interests tend to determine whether people have access to medicines (for malaria or HIV/AIDS, for example).

Ultimately, historical and political factors determine the type of medical care available in a given country. Biomedicine – defined as medicine based on biological science – is dominant in Western industrialized countries. In Africa, Asia and Latin America, its history is closely linked to the violent colonial past. In these parts of the world, people often rely on a wide variety of forms of health care (including “traditional” practitioners, religious healers or medical systems such as Ayurveda or homeopathy). These options coexist with biomedicine. Of course, there is also a growing market for spiritual or alternative medicine in Western countries, but the difference is that these options are particularly used by wealthier patients.

Medical anthropology and global health

The field of global health has created new challenges and opportunities for medical anthropology. “Global health” has become a growing field of work and study. Universities around the world have launched programs on the subject. Medical anthropologists participate in various multidisciplinary collaborations. Others work for one of the many international health organizations in this field.

An important aspect of medical anthropology research regarding global health is the ability to translate different social and cultural contexts. Medical anthropologists delve deep into local communities in long-term fieldwork, gaining the confidence to understand how people engage with specific treatment or prevention services – or why they reject them altogether. response, for example, to new health challenges such as Covid-19.

Medical anthropology also reveals what resources individuals mobilize, depending on their circumstances, when faced with potentially fatal or chronic illnesses. It also shows the role played by new and old solidarity networks (family, religious and other communities).

At the same time, medical anthropology clearly shows which groups suffer the most discrimination in a society, such as those with disabilities or stigmatized illnesses like HIV/AIDS. Researchers can also determine which medical, physical, psychological and linguistic services would best meet the specific needs of marginalized people.

Ultimately, medical anthropologists are not only focused on the mechanisms of health care themselves and how treatment, care, and prevention can be improved in general. They also pay attention to the social context and its underlying implications. Raising awareness and implementing prevention programs and vaccination campaigns aimed at reaching people of different ages, genders and social backgrounds can benefit from such research.

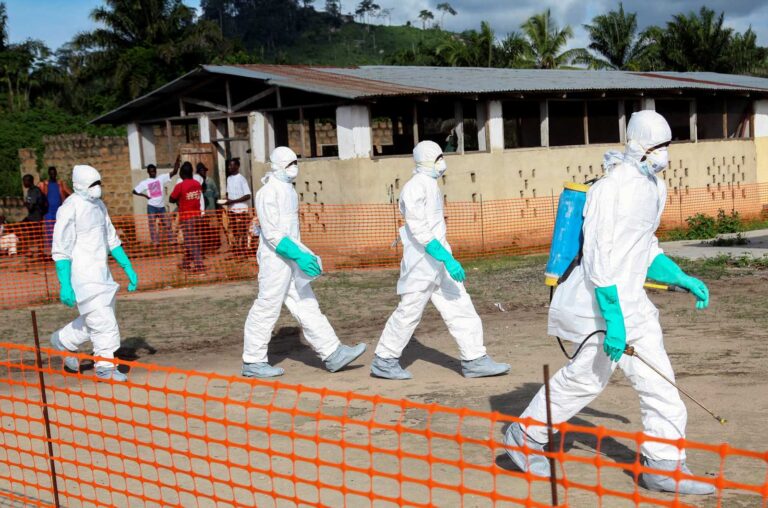

Government and non-governmental action in the face of new epidemics also demonstrates the challenges health organizations face in a globalized world. In particular, the “emergency responses” of international organizations to epidemics like Ebola have shown that affected societies in resource-poor contexts often deeply distrust such interventions. Organizations generally take too little time to address specific local conditions and needs and are therefore often implicated in the long history of colonial and postcolonial domination.

In all of these situations, medical anthropologists are able to act as mediators between different contexts, helping to build mutual trust. They focus on the resources and action potential of individuals and local communities – everywhere.

The references

Dilger, H. and Hadolt, B. (eds.), 2010: Medizin im Kontext: Krankheit und Gesundheit in einer vernetzten Welt (“Medicine in Context: Illness and Health in a Networked World” – in German). Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang.

Yates-Doerr, E., 2019: What global health for whom? A disturbing collaboration with careful equivocation. American Anthropologist 121, 297-310.

Hansjörg Dilger is professor of social and cultural anthropology and head of the research area Medical Anthropology/Global Health at Freie Universität Berlin.

hansjoerg.dilger@berlin.de