Summary

- A haunting in Venice is Kenneth Branagh’s latest Poirot crime film, based on the novel by Agatha Christie. It adds supernatural elements and explores Poirot’s mental health.

- Branagh’s Poirot films tackle mental health issues without an agenda, portraying Poirot as a progressive character. The films balance great storytelling with realistic representation.

- Poirot’s character quirks, such as his obsession with symmetry and his mustache, are traumatic responses stemming from his wartime experiences. Mental health and PTSD play a significant role in one’s character development.

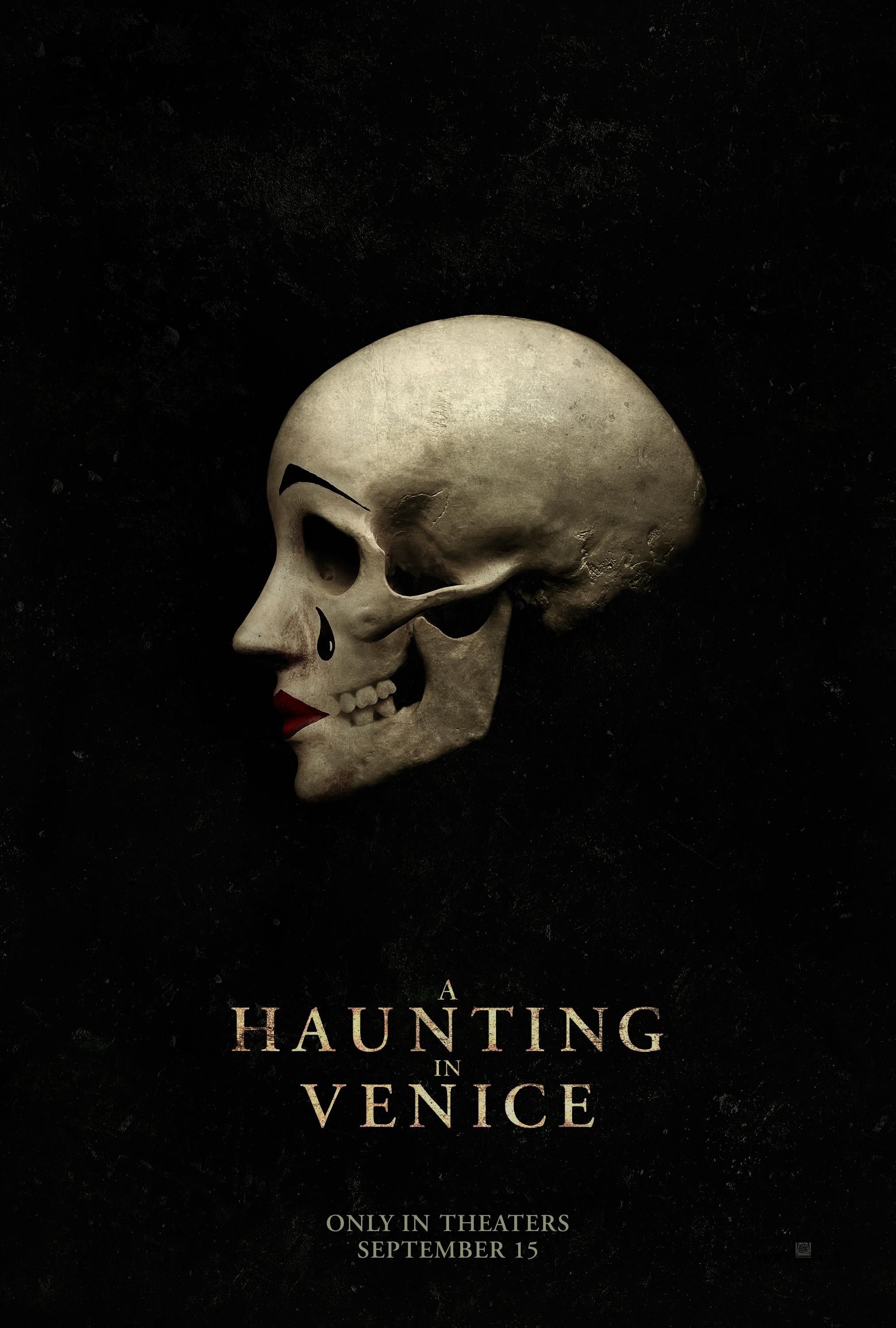

A haunting in Venice is the latest of Kenneth Branagh’s Poirot crime films, in which he plays the legendary detective himself. It is based on a novel called Halloween Party by the legendary Agatha Christie, considered one of the greatest crime writers of all time. A haunting in Venice sticks to Christie’s story while adding a few more supernatural elements and the underlying story of Poirot’s sanity.

Branagh’s Poirot films surprisingly focus on mental health issues, but not in a negative way. Hercule Poirot is cast as a more progressive character, while others have differing opinions on mental health issues and politics depending on their character type. This allows for realistic representation without the feeling of agenda compared to grand storytelling, even if there are changes of A haunting in Venicethe source material. Although this is not the main focus of the films, given that people are being murdered, it is a poignant aspect of the storytelling that “stands out like the nose in the middle of a face (Murder on the Orient Express).”

Poirot’s character’s quirks are responses to trauma

As viewers see Hercule Poirot’s ‘quirks’ minutes later Murder on the Orient Expressit is only afterwards, Death on the Nile, let them learn why he has them. He measures his eggs to see if they are the same size, worries about removing a pastry from his table so that there is an equal quantity, and regularly asks people to straighten their ties if they are crooked. These appear as ongoing gags, but are actually traumatic responses. Although not directly stated, there is plenty of reason to believe that Poirot suffers from OCD and PTSD from the war. With the first two films set in the 1930s, mental health issues were not as openly diagnosed or talked about due to the stigma surrounding the subject. Even though an overwhelming number of soldiers suffered from post-traumatic stress and mental health issues, society was content to talk about this as the effects of war. Even Poirot’s iconic, exaggerated mustache grew because of his war trauma. Poirot is wounded in battle, leaving him with a scar on part of his face, so his lover, Katherine, suggests that he grow a mustache to hide it. He ends up sporting the same style as his commander in honor of his death, for which Poirot is haunted and for which he is responsible. Honestly, his love of pastries seems to be a character quirk, perhaps to accompany his Belgian heritage and to balance his pretentious traits with endearing and endearing traits.

Poirot only became a detective after the war, and the profession came to him more than he sought it. Asked about her brilliant methods of deduction, Poirot describes her as being capable of “only see the world as it should be. And when this is not the case, the imperfection stands out like the nose in the middle of a face. This makes most of his life unbearable, but it is useful for detecting crime. (Murder on the Orient Express).” Poirot views less favorably the same traits that others admire him for, but has learned to use them to his career’s advantage. Poirot admits to being vain and liking having his intelligence admired. He clings to these traits to distract him from intrusive thoughts about the These are traits that hide his vulnerability from others but give him external validation from them.

Poirot’s wish is to escape his life as a detective and retire to a peaceful place. In Death on the Nile, he announces to Salomé Otterbourne that he wants to buy a house with a vegetable garden. When she asks about relationships, he behaves socially awkwardly and distracts her thoughts by saying he has his job and books to keep her company. It’s only in his retirement that he realizes he can’t stay away from solving mysteries. They are like a constraint on which he must act, but in A haunting in Venice, Poirot seems to accept this part of himself. He even grows enough as a character to shave his mustache, openly showing his scar, to visit Salomé Otterbourne at her club to ask her out at the end of Death on the Nile.

Poirot’s empathy for Dr. Ferrier is a sign of growth

In A haunting in Venice, Poirot meets Dr. Ferrier, the Drake family’s family doctor, shaking nervously against a wall. His volatile behavior immediately makes him suspicious until it is revealed that he was also a war medic. Poirot makes a simple statement to Dr Ferrier, saying: “Battle scars are not always on the body,” showing the audience and the doctor that Poirot sympathizes with his pain because he too was in the war and lives with PTSD. A haunting in Venice allows viewers to see Poirot’s vulnerability, which the previous films mostly alluded to. This does not make Ferrier a suspect for Poirot, but it helps to better understand the character when conducting the investigation.

Dr. Ferrier and Poirot share many things in common. They both fought in a world war, have unattainable love, and are experts in highly intelligent fields. The difference is that Poirot’s detective prowess was created from his war experience, while Ferrier was weakened by his. He was the family doctor who cared for Rowena Drake’s daughter while she was ill and remained after her death due to his lingering feelings for Rowena. Ferrier has a son, Leopold, who cares more about his father than the other way around, which shames Ferrier. This does not seem shameful to Leopold, however, who shows much empathy for Ferrier in his attention.

Although Rowena seems to understand Ferrier’s plight, she could be guided by guilt as she is with her daughter because she never returns his feelings. Maxime, the ex-fiancé of Rowena’s daughter, is the most stigmatizing character. He berates Ferrier’s condition, causing an episode of PTSD and a tantrum, fighting Maxime, thinking he is an enemy soldier, until his son calms him down, reminding him that he is at the orphanage with him, no return to war. This scene is so quick that it might go unnoticed, but it’s a well-acted and heartfelt depiction of the impact of his PTSD on his daily life. This is not, however, exclusive to Dr. Ferrier, because Rosalie Otterbourne in Death on the Nile calls Poirot as “obsessive…alone for a reason…little monster” after Bouc’s death. She says these words out of the anger and sorrow of the moment.

Bouc wanted Poirot to be happy one day because he knew that even Poirot didn’t like being in detective mode all the time, but Rosalie “I didn’t want him to be happy“She wanted him to find the killer. She thought he would only be happy if he overcame trauma, but that would mean he wouldn’t be the great Detective Poirot that she and others wanted. is selfish and a misunderstanding, but it’s a real character flaw in a generally good person, which reflects an honest stigma, just like Maxime in Ferrier.

From A haunting in Venice set in 1947, ten years after the first two films, shifting the focus from Poirot’s mental health to others could be a way of showing that he has healed over time. He can help others with much more than his detective skills, although characters who don’t identify may not see it. A haunting in Venice could have tied a nice bow to Branagh’s Poirot films, with the character actually being removed for part of the film. Poirot’s inability to retire means that audiences can look forward to seeing future Poirot films with colorful new castings and, of course, more murder.

A haunting in Venice

In post-World War II Venice, Poirot, now retired and living in his own exile, reluctantly attends a seance. But when one of the guests is murdered, it’s up to the former detective to find the killer.

- Release date

- September 15, 2023

- Cast

- Kyle Allen, Kenneth Branagh, Camille Cottin, Jamie Dornan, Tina Fey, Jude Hill, Kelly Reilly, Michelle Yeoh

- Rating

- PG-13

- Duration

- 103 minutes

- Gender

- Crime, Drama, Horror

- Writers

- Michel Green

- Story by

- Agatha Christie

- Prequel

- Death on the Nile