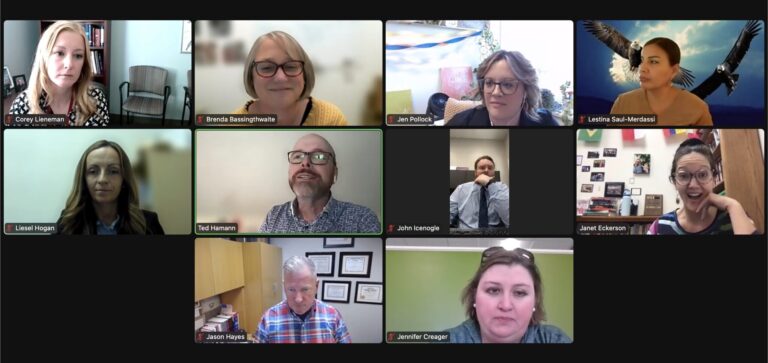

LINCOLN — A Nebraska civil rights panel continued Wednesday to look at the effects of COVID-19 on K-12 education with a focus on youth mental health.

This was the third public meeting of the Nebraska Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, charged with determining the civil rights implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and possible recommendations to the national panel. The advisory committee hosted two forums this summer, including one on Online learning and the digital divide in Nebraska.

Jen Pollock of the Nebraska School Psychologists Association said there is a serious workforce shortage nationwide, especially in education. Yet teachers cannot be expected to be experts in mental health.

“They are content experts, and that’s what we need,” Pollock said.

Schools could, however, have a multi-tiered support system, which Pollock says includes creating safe classroom environments and positive relationships with students, reinforcing clear and high expectations, and adopting rigorous teaching.

“There are never too many adults”

Liesel Hogan, a licensed mental health practitioner who works in Educational Services Unit #3 with Pollock, said the impacts of shortages have direct impacts on students. ESU #3 is Largest ESU in Nebraskaserving 18 school districts.

Schools need relationships, and trust and rapport between students and teachers is essential, Hogan added. If there are no relationships, students perform less well and teachers can feel like “glorified babysitters,” according to Hogan.

“I always say that you can never have too many adults who can love a student in order to get them back to where they need to be from a functional standpoint,” Hogan said.

The pandemic has also led to more anxiety, more school absences and a fear of the unknown, with fewer students willing to learn to drive or leave their homes for social interactions. Many students feel a lack of motivation, she explained, because many activities have been disrupted during the pandemic.

“An object in motion stays in motion,” Hogan said.

Increased mental and behavioral concerns

Corey Lieneman, assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, said that since COVID-19, there has been a 25% increase in anxiety and depression globally .

Nationally, about 20% of youth ages 3 to 17 suffer from at least one mental or behavioral health disorder, and suicide is the second leading cause of death among children ages 10 to 14, a Lieneman said. The suicide rate among children aged 12 to 17 more than doubled between 2008 and 2020.

Brenda Bassingthwaite, an associate professor at UNMC’s Munroe-Meyer Institute for Genetics and Rehabilitation, said that each year it has become more and more difficult to seek counseling in a school setting.

Indeed, because students’ needs are not met, it is more difficult for them to develop new skills, Bassingthwaite explained, and students instead adopt inappropriate behaviors, such as destroying objects or climbing on tables to attract attention. attention or access other opportunities.

“When we don’t respond quickly to students’ needs, those needs often increase and become more difficult to meet,” she added.

Labor shortages can lead to classroom closures. This year, Omaha Public Schools transferred children with special educational needs to different schools due to a shortage of specialist teachers in three buildings. Even though there may be no other options, Bassingthwaite said, there will still be an impact on students.

Information overload

There is also information overload among adolescents, Lieneman said, whose brains are not yet developed to the point where they can absorb all the information presented to them.

For example, students haven’t been able to fully understand the technological implications during the pandemic or understand the virus itself, said Lestina Saul-Merdassi, a behavioral health counselor, youth program director and certified advocate at the Nebraska Urban Indian Health Coalition.

The increase in technology use, accelerated by COVID-19, may also be a concern, Lieneman said. She noted that her middle school child will take nearly 20 classes during the calendar year and that most, if not all, will have an online component with many links per class.

Lieneman proposed some solutions to simplify education, such as:

- Remove or reduce certain assignments.

- I start school later today.

- Increase recreational and social opportunities.

- Reduce the use of technology.

- Set developmentally appropriate expectations.

- Prioritize sleep, healthy eating and physical activity.

Despite the challenges, Lieneman said, all panelists touched on similar topics, suggesting a unified goal to improve student and teacher outcomes.

“It’s reassuring to know that we all see the same things, and it helps me feel like we’re part of a team,” Lieneman told the group, “and we’re going to be able to accomplish something together.” a state.”

Members of the public may provide written comments to the Nebraska Advisory Committee before members submit a report to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Comments can be sent to Victoria Moreno at (email protected) no later than December 8.

GET MORNING NEWSPAPERS IN YOUR INBOX