As the world experiences unprecedented population growth and ever-increasing ecological pressures, the topic of preserving natural resources in Chinese medicine is attracting increasing attention from practitioners. The holistic nature of Chinese medicine tends to attract people who are passionate about ecological sustainability, and the constant stream of alarming media reports about pollution in China keeps the topic of TCM ecology in the spotlight for many clinicians and patients. Practitioners are frequently confronted with questions from patients and media reports about pesticides, contaminants, and endangered species in the Chinese medicine industry, and too often we fail to effectively clarify the facts surrounding these issues at the community around us.

Most Western practitioners turn to Chinese medicine because we want to help patients. This is why our exams and schools tend to naturally focus on clinical knowledge rather than specialist disciplines such as herbal medicine. Although practitioners are often passionately concerned about the quality, safety and ethics of the herbs they prescribe, the precise origins and growing conditions of the dried and sliced Chinese herbs found in pharmacies remain shrouded in mystery. for many practitioners. By better understanding the origin of our herbs, we can better communicate with our patients about important issues related to herb safety and ecology.

Preserve plant resources

Protecting the planet’s natural resources is essential to the long-term future of Chinese medicine. In ancient times, wild plants were widely used in Chinese medicine, and many herbs remain primarily harvested from wild sources. Although many medicinal herbs remain abundant in nature, growing demand and limited limits on wild populations have spurred their cultivation for centuries.

In some cases, plant resources have been insufficient throughout history. For example, wild Asian ginseng was originally found over a relatively wide geographic area in China before the Song Dynasty, but some of the ginseng-producing regions praised by ancient texts no longer have intact populations of wild ginseng. . As Asian ginseng became increasingly rare, codonopsis and American ginseng emerged as substitutes, and both herbs entered the materia medica literature simultaneously in the mid-18th century. Wild ginseng hangs by a thread in northeast China, largely thanks to the closure of vast forest areas by imperial decree in Qing Dynasty. Today, all Asian ginseng used clinically in Chinese medicine comes from cultivated sources, and true wild specimens are extremely rare.

Nowadays, more than 150 common Chinese herbs are mainly derived from cultivated plants. Many herbs have been cultivated for centuries, such as Bai Zhi, Di HuangAnd Huang Lianand numerous ancient documents describe their ideal growing regions, characteristics and processing methods.

Over time, new growing techniques have emerged, such as using cell culture to propagate plants that cannot be easily grown by seed. Herbs such as Bai Ji, Tian MaAnd Shi Hu are grown in glass jars using cell culture, which has brought Shi Hu And Tian Ma from the threat of extinction and will contribute to preserving that of Bai Ji wild resources. Other herbs, like Fu Ling, benefit from sustainable harvesting methods using terraced pine trees inoculated with the poria fungus, eliminating the need to damage wild pine trees. While most easy-to-grow plants have been grown for centuries, these innovative techniques make it possible to grow technically difficult plants that would otherwise be unsustainable due to their limited wild resources.

As practitioners, our patients often ask us about endangered species in Chinese medicine. In the media, our patients have heard about cases such as the recent endangered species sting which lasted six months and resulted in a £20,000 fine for a major TCM company in central London , while the true story of how London police managed to waste six months of endangered species. Species control resources on a few bottles of pellets made from obviously cultivated plants go unnoticed. One can’t help but wonder to what extent ivory trafficking could have been prevented if a literature review or even a decent Google search had been considered before going after the crime. Mu Xiang granules.

Certainly, we cannot solve all the perception problems regarding Chinese herbs and endangered species overnight, but we can save our patients a lot of trouble and stress by being well informed about the ecological context of the herbs we let’s use.

Preserving medicinal authenticity

The art of identifying authentic medicinal substances has been at the heart of quality control in Chinese herbal medicine for millennia. Although illustrated texts and written descriptions have been used for over a thousand years to convey knowledge about identifying Chinese medicines, avoiding misidentified herbs and inferior products has been a problem for herbalists throughout the story. As a result, traditional techniques developed over centuries to identify Chinese medicines based on their macroscopic characteristics remain very relevant today.

Writing in the 6th century AD, the physician Tao Hongjing summed up the challenges of the ancient herb market in the following timeless quote: “Many doctors do not recognize medicines and only listen to the sellers; the sellers are not experts and trust those who collect and distribute (the medicines). Those who collect and distribute rely on inherited (knowledge) and cannot distinguish the authentic from the inauthentic, the good from the bad. As practitioners in the modern era, we have the luxury of being able to choose from many reliable suppliers with excellent quality control practices, but we must nevertheless remain proactive in minimizing the extent to which Tao’s statement rings true today. ‘today.

Today, the Chinese Pharmacopoeia serves as the guiding authority on the official botanical origin of the most common Chinese medicinal materials, and it also provides the standard testing methods used for their identification. Another fantastic resource is the Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards series, which stands out as one of the most freely accessible and authoritative sources of information on the authentication of Chinese medicines; the monographs are available free online here: www.cmd.gov.hk/html/eng/service/hkcmms/cmmlist.html

In China, authenticated reference standards for Chinese herbs are provided by the National Institute of Drug Control (NIDC) for use in analytical testing and confirmation of botanical identity. China’s GMP manufacturing laws for herbal products, like those in the United States, emphasize the correct botanical identification of plant materials used, and manufacturers such as pellet extract companies routinely use thin layer chromatography (TLC) to identify over 400 individual herbs. .

The importance of authenticating medicinal materials and maintaining voucher specimens is emphasized in current NIH guidelines for herbal medicine research, and many U.S.-based groups are currently developing authentication resources. The United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) and Chinese Pharmacopoeia recently announced an increased level of cooperation to advance quality control standards, and the USP’s recent decision to create monographs on medicinal plants instead of just dietary supplements marks a historic milestone. In addition, a number of other American organizations have been very active in the field of botanical identification in recent years, including the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (AHP), and the American Botanical Council (ABC).

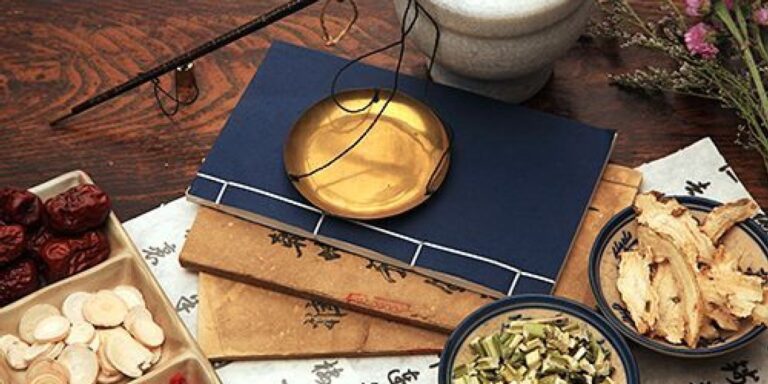

Preserving the culture of materia medica

In addition to preserving the physical resources of Chinese herbal medicine, such as wild plant reserves and the best growing environments, the culture surrounding Chinese materia medica literature is worth preserving. For centuries, encyclopedic texts of materia medica have recorded knowledge about the quality of medicinal plants, their processing, regions of cultivation, and their clinical applications, and these texts illustrate a cultural tradition of scholarship that endures to the present day .

We are fast approaching the 500th anniversary of Li Shizhenthe author of Ben Cao Gang Mu (Grand Compendium of Materia Medica). THE Ben Cao Gang Mu represents the pinnacle of traditional Chinese literature on materia medica, written on the basis of That of Li Shizhen extensive personal travel and extensive textual research. More than just a herbal encyclopedia, Li used the Ben Cao Gang Mu to illustrate a comprehensive and innovative approach to the classification of nature as a whole, recording knowledge that remains relevant across many disciplines to the present day.

As Chinese medicine gains popularity in the West, we must strive to preserve the tradition of scholarship that constitutes the essence of materia medica research, just as we protect the plants themselves.

The references: