Twelve years ago, at a conference at St James’s Palace, Prince Charles told an audience that he “felt proud” of having once been called an “enemy of the Enlightenment”.

Edzard Ernst

Revisiting traditional thinking before about 1650 clearly appealed to the heir to the throne – reaching back to a time before Locke, Voltaire, Descartes and Hume embraced reason over traditional practices.

During this time speechCharles spoke of his philosophy of “being part of nature, understanding the need to blend the best of the ancient with the best of the modern.”

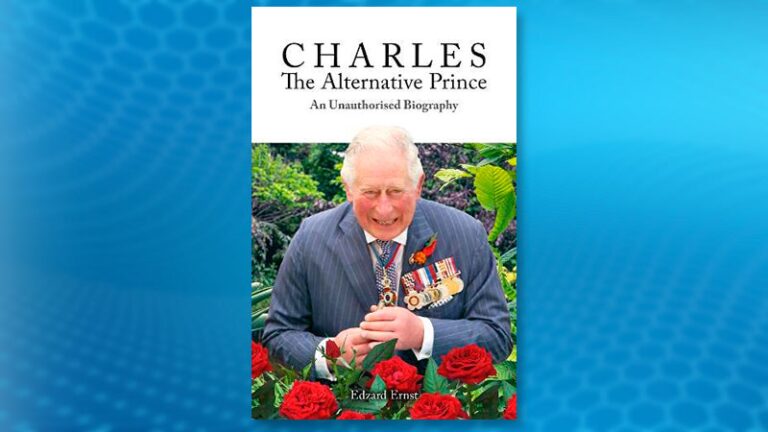

The belief that the “order of nature” must take precedence over science and evidence underlines the Prince of Wales’s foray into the world of medicine, he says. Professor Edzard Ernst MD, in a new book, “Charles, The Alternative Prince – An Unauthorized Biography.”

As the world’s first professor of complementary and alternative medicine, based at the University of Exeter, Ernst has qualified to assess what he calls “Charles’s love affair with alternative medicine”.

Ernst explained to Medscape United Kingdom: “I have dedicated my professional life for the last 30 years to research into alternative medicine. Prince Charles is probably the world’s strongest advocate for this part of healthcare, so it was a very obvious choice for me. “

The author argues that instead of building on his privileged position and realizing his personal vision of integrating conventional and alternative medicine, the prince “pursued a largely anti-science agenda and promoted integration without reserve of unproven treatments in the NHS”, with the result that “it has become an obstacle to progress in healthcare and has generated more harm than good”.

Shake up the medical establishment

The omens were not good when, newly elected short-lived president of the British Medical Association for its 150th anniversary, the Prince of Wales did not come to praise the medical luminaries assembled with the “usual niceties”, but to launch “an all-out frontal attack”, says Ernst, in which he lectured them that ” the entire imposing edifice of modern medicine, despite its breathtaking success, is like the famous Tower of Pisa, unbalanced.

Rather than persuading his audience of the benefits of integrating alternative and modern medicine, his speech had the opposite effect. “Being lectured like first-year medical students by a clearly ill-informed young man would hardly have amused the experienced doctors,” comments Ernst.

“Charles’ explosion therefore risked constituting a counterproductive step backwards by reinforcing the barriers which had practically disappeared,” he writes. “This affront has led to a reluctance on the part of the British medical establishment to look favorably on alternative medicines.”

Public disagreement with Charles

It should be noted that the author of “Charles, The Alternative Prince” has a long history of public disagreement with the Prince’s views on integrative medicine. In fact, he holds Charles responsible for the deterioration of his position at Exeter, leading to his early retirement.

The row dated back to 2005, when Charles personally commissioned Christopher Smallwood, former chief economic adviser at Barclays bank, to examine the effectiveness of certain complementary therapies in a bid to persuade the government to offer more on the NHS.

Edzard Ernst

The report, which has never been peer-reviewed, concluded that there was sufficient evidence to show that some complementary therapies may be more effective than conventional approaches to treating certain conditions, and called for an assessment by NICE.

Ernst was made aware of the draft document which he said contained “many serious errors”. He then argued that Charles “could have overstepped the bounds of his constitutional role by attempting to influence British health policy”.

Write in the British Journal of General Practice In 2006, Ernst said of the Smallwood report: “One gets the impression that its conclusions were drawn up before the authors had searched for evidence that might match them. »

A formal complaint lodged by Charles’ first private secretary with the University of Exeter “alleging that I had breached confidentiality rules, led to the closure of my research unit”, according to Ernst.

Is Ernst’s book a period of recovery for Charles and those around him? “No, that’s one of the main reasons why I hesitated for years to write this book, because it could be seen as an act of revenge for what happened then,” he says. “I think anyone who reads the book will realize that I mention these two or three unpleasant encounters with Prince Charles and his supporters for the sake of completeness.”

Ernst was by no means alone in his criticism of the Smallwood report. In a letter to The GuardianDr Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of The Lancetwrote: “We are losing our grip on rational, scientific medicine that has benefited millions and is now being eroded by the complicity of doctors who should know better and a prince who seems to know nothing at all. “

Royal intuition versus rational brain

The book explains how the Prince of Wales developed his views on alternative medicine, focusing on the influential role played by South African writer Sir Laurens van der Post.

Ernst tells us that “in his youth, he fell under the spell of van der Post who introduced him to very strange ideas: mystical thought, Jung, psychoanalysis, etc., etc., and this put him on the path to follow his intuition, rather than his rational brain.

In the book he writes: “Charles was searching for the meaning of life and Laurens was good at providing him with a “missing dimension”. Ernst argues that “Charles’ arts degree left him ill-equipped to understand science or medicine, so Laurens convinced him that his royal intuitions came ‘from a source far deeper than conscious thought'”.

The author points out that van der Post’s reputation imploded after his death. His biographer, JDF Jones, describes him as a “compulsive fantasist” whose “ability to present a false image to others was coupled with a tendency to overestimate his own abilities.”

Homeopathy

We also learn that the royal family believed in homeopathy for a long time, dating back to the 1830s, culminating in the appointment of Prince Charles as patron of the Faculty of Homeopathy in 2019.

A report of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee in 2010 concluded that homeopathic remedies worked no better than placebos.

In 2017, NHS England said it would no longer fund homeopathy within the NHS because the lack of evidence of its effectiveness did not justify the cost. The decision was supported by a High Court judgment in 2018.

For Professor Ernst, this decision is further proof that success in promoting alternative medicine is elusive. “When Charles first sided with homeopathy, the UK had five NHS homeopathic hospitals; today, none bears that name,” he says. While the prince’s attempts to secure regulatory status for British homeopaths, herbalists and acupuncturists failed, as did his vision of a model hospital for integrated medicine.

Among other themes in the book, he analyzes Charles’s promotion of osteopathy and chiropractic, herbal medicine, Gerson therapy, and the Foundation for Integrated Health, which was created to promote the prince’s views and which was replaced by the Faculty of Medicine.

For Ernst, “Charles acts according to his intuition, his beliefs, his convictions” and “seems totally immune to evidence that does not confirm his credo. In this, he can become a real enemy of the age of reason.”

“He has no expertise in science or medicine and only takes advice from people who agree with him first and foremost.”

He concludes: “When Charles contradicts the consensus, when he uses his influence to interfere with our health care, and when he claims that his opinion constitutes evidence, he obstructs progress.”

What could happen when the longest-serving Prince of Wales becomes king?

“He answered this question himself,” Ernst tells us. “We asked him if he would continue to lobby, and he said: ‘certainly not, I’m not that stupid’.”

He adds: “I suspect it will stop visibly, and it will continue in secret.”

“Charles, The Alternative Prince” is published on February 1, 2022 by Imprint Academic.